At the Cheltenham Festival in 2019, Bryony Frost became the first woman ever to win a Grade 1 jump race at the meeting when she took Frodon across the finish line first in the Ryanair Chase. As a year, it matched 2018 for wins by female jockeys, with two wins for Rachael Blackmore and one from Lizzie Kelly, meaning that four races over the course of the Festival were won by female riders. The difference in 2018 is that it was four different female jockeys that found themselves on the proverbial winners’ podium, with Katie Walsh also getting in on the act.

At the Cheltenham Festival in 2019, Bryony Frost became the first woman ever to win a Grade 1 jump race at the meeting when she took Frodon across the finish line first in the Ryanair Chase. As a year, it matched 2018 for wins by female jockeys, with two wins for Rachael Blackmore and one from Lizzie Kelly, meaning that four races over the course of the Festival were won by female riders. The difference in 2018 is that it was four different female jockeys that found themselves on the proverbial winners’ podium, with Katie Walsh also getting in on the act.

The win for Frost moved female jockeys into the limelight, however, with many being amazed that it had taken so long for one to win a Grade 1 race at the Cheltenham Festival. After all, Nina Carberry had already broken the Grade 1 barrier when she won the big bumper at Punchestown in 2006 and Caroline Beasley won the Foxhunter Chase in 1983, becoming the first woman to win a race of any description during the Festival meeting. The natural question, therefore, is about whether or not women are truly respected for their role in racing and what the future holds for them.

The Female Pioneers of Racing

Horse racing remains a sport that is dominated by the male participants, at least as far as the jockeys are concerned. Female trainers have been respected in the industry for decades, but it remains the case that being a jockey is something of a boy’s club.

That is the case in spite of the fact that there’s no reason why male and female jockeys can’t compete alongside each other in the same way that there are rules splitting up the genders in, for example, football and tennis.

Who, then, were the women that blazed a trail for others to follow?

Alex Greaves

There are a number of women who have been paving the way for their fellow riders, not least of all Alex Greaves. Greaves became the first woman to ride a horse in the Epsom Derby when she sat on the back of Portuguese Lil, a 500/1 outsider in 1996. She finished twentieth but didn’t allow that dampen her spirits, following it up a year later by becoming the first woman to win a Group 1 race in the United Kingdom when she rode Ya Malak to a dead-heat in the York Racecourse Nunthorpe Stakes.

Hayley Turner

Any hopes that Greaves had broken through the glass ceiling and others would follow suit were soon dashed, however, and it took sixteen years before another female jockey would take part in the Epsom Derby. That female jockey was Hayley Turner (pictured above), who won one hundred flat races in 2008 and three Group 1 races during her career.

Diane Crump

The success of both Greaves and Turner would not have been possible without the women that came before them and Diane Crump deserves more credit than most. She became the first female jockey to take part in a thoroughbred race when she rode Bridle ’n Bit at Hialeah Park Race Track in 1969, requiring a police escort to make it through the crowd. She followed that up three years later by becoming the first woman to take part in the Kentucky Derby.

Caroline Beasley

We’ve already mentioned Caroline Beasley for her part in becoming the first woman to win a race at the Cheltenham Festival, but she deserves far more credit than just that. As an amateur rider, she also scored over fences at the Grand National course when she led Eliogarty to victory in the Fox Hunter’s Chase in 1986. She went on to become a successful point-to-point trainer.

Gee Armytage

Few women have done as much to alter the perception of females in the sport of horse racing as Gee Armytage. She led the Ellier to a Cheltenham Festival win in 1987, becoming the second woman to win a race at the meeting, but more importantly she also won on the back of Gee-A and ended up tying with Peter Scudamore in the overall jockey rankings for the week, losing out only because of a count back to look at their placed efforts.

Katie Walsh

Katie Walsh won her first race in 2003 when she guided a horse named Hannon to a first-place finish in a race at Gowran Park. She enjoyed a Cheltenham Festival double in 2010 thanks to wins on Poker De Sivola and Thousand Stars and became just the third female jockey to ride to victory in the Irish Grand National on Thunder and Roses, but it was her success on Seabass in 2012 that sees her name on this list. She took the horse to a third place finish in the Grand National at Aintree, becoming the first woman to place in one of steeplechasing’s hardest races.

Female Representation in Racing

Knowing about the women who paved the way for others in the horse racing industry is one thing, but how much female representation is actually present in the sport? We know that men dominate the industry, but are female jockeys under-represented when compared to their male counterparts or is it about even?

According to the British Horseracing Authority, there are about four hundred and fifty jockeys that are licensed to race in Britain, as well as closer to three hundred amateur riders. A quick search of the BHA’s database presents you with a list of seven hundred and seven jockeys in total.

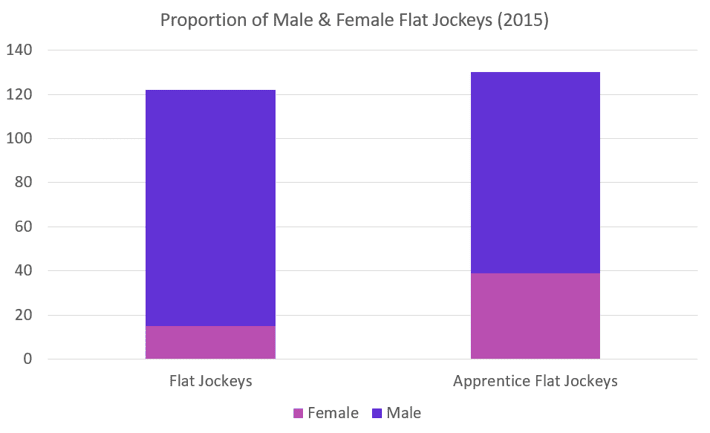

In 2015, around 20% of the two hundred and fifty-two flat racing jockeys were women, which amounted to approximately fifty-four female riders.

If you assume that the figures didn’t rise significantly over the years that followed, that would equate to about one hundred and forty jockeys across both disciplines going on the BHA’s number of registered jockeys.

Why Aren’t There More Female Jockeys?

Is 20% of all jockeys being women enough? Obviously that’s a difficult question to answer without having a clearer idea of how many females are applying to become jockeys in the first place. It’s also the case that a mere 11.3% of professional jockeys are female, with the other 8.7% being made up of amateur riders. Perhaps part of the reason why there aren’t as many female jockeys as there are males comes down to how many trainers offer them opportunities.

A recent study by the University of Liverpool discovered that there is little difference in the ability of male and female jockeys, with the study taking into account the quality of the horses being used by the riders across fourteen years. Jockey Gemma Tutty believes that women are ‘are a disadvantage’ because there are some trainers that simply refuse to use women jockeys.

It’s not that women are under-represented in the industry as a whole, with 42% of stable staff in 2010 being women and that figure had risen to 51% by 2018. Yet female jockeys are still not trusted by trainers to do the job on the biggest horses, with just 5.2% of the 1.25 million individual rides looked at in the study having a female jockey. If trainers aren’t willing to trust women to ride their horses despite the fact that the stats suggest they’re just as capable, fewer women will look at it as a serious career for them to make headway in.

What Can Be Done to Encourage More Female Jockeys?

Given the state of play in terms of representation for female jockeys, the natural next question is about what can be done to encourage more women to become riders. A study by Oxford Brookes University found that women outnumbered men by 70% in terms of those entering the race profession from college courses, but that their careers stagnated quickly. With women comprising just 16% of senior board positions in British horse racing organisations it’s perhaps no surprises that there remains a ‘boy’s club’ feel to the industry.

One thing that might see a shift in the current thinking will be if the British Horseracing Authority follow the lead of their French counterparts. From the first of March 2017 female jockeys were given a two kilogram allowance in France, with the aim of allowing women to hold a more prominent role in the sport in the country. The result was a two-fold rise in the number of female jockeys starting flat races in France that was coupled with a 165% increase in female winners.

It is likely that the BHA will consider something similar in the not too distant future, with the Chief Executive of the organisation, Nick Rust, saying that there is a degree of pride that men and women can compete equally in British horse racing, but that ‘if female jockeys are not being given the same opportunities as men, then this cannot be considered as equality’.

Another thing that is likely to shift the dial towards more female participation in the sport is the 2017 introduction of the Silk Series, which is a championship exclusively open to women. It was an Arena Racing Company initiative, with a prize pot of £100,000 for the 2017 season and it involved nine ARC owned racecourses giving themselves over to female jockeys for racing on Ladies Day.

The winning jockey at the end of the series is awarded the Tufnell Trophy, which was named in honour of the first woman ever to take part in a horse race in the United Kingdom in 1972, Meriel Tufnell. By 2019, the series had expanded to be run over thirteen racecourses and the total prize fund reached £150,000. It was restricted to flat racing when the series was first launched by it’s likely that that will be expanded to jump racing as it becomes more popular. The participating racecourses for the 2018 series were as follows:

- Musselburgh

- Chepstow

- Great Yarmouth

- Lingfield Park

- York

- Newcastle

- Royal Windsor

- Hamilton Park

- Brighton

- Bath

- Goodwood

- Wolverhampton

- Doncaster

The Future for Females in Racing

What lies in store for female jockeys remains to be seen, but Nick Rust believes that there could be a female champion jockey within five years, such is the extent to which the opportunities are opening up for them. If the BHA follows the lead set by the French and makes a ruling to give female jockeys weight, then it’s likely that trainers will start using them more too.

There is still a battle over hearts and minds, however. An online poll into the Silk Series initially showed that respondents were not keen on seeing more all-female racing events, but in many ways that is just a reflection of a society that voted down the release of Captain Marvel in the cinema on Rotten Tomatoes because it had a female lead. Sinead Kissane believes that the first place to start is by stopping the reference to them as ‘female professional jockeys’ and just call them ‘professional jockeys’ instead.